Jean-Claude Van Halen

The scents of a murky narrative were lingering in the atmosphere; the haze of a cursed tale drifting and dispersing in rolling tableaus of past pain, past turmoil and pasta. The restaurant - a particularly upmarket hive of vanity just off Euphemism Boulevard - was soaping with the suds of

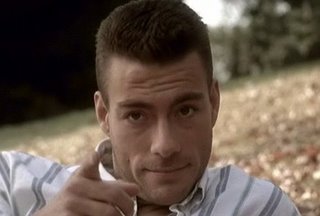

The scents of a murky narrative were lingering in the atmosphere; the haze of a cursed tale drifting and dispersing in rolling tableaus of past pain, past turmoil and pasta. The restaurant - a particularly upmarket hive of vanity just off Euphemism Boulevard - was soaping with the suds of Amongst these secondary recesses, these fjords of the downtrodden and despondent, perched actor Jean-Claude Van Damme. Most of his body was shrouded in thick strips of bandage, from the base of his feet to the peak of his cranium. A diagonal collage of first-aid pride did dance all over his person, with only the occasional relenting gap. His eyes for one were unsheathed; as were his knuckles. He sat with the faxed draft of some film-industry whiz-kid’s scribbles on his lap, intermittently flexing strange contortions in his eyes.

Opposite him was seated his agent, vacuumed scalp and air-brushed face, with a look of sheer astonishment lashing his jowls. Mouth slit slightly in amazement, he motioned towards Van Damme. Upon catching sight of this, the Belgian feverishly roared, “What is this nonsense supposed to be? ‘Big return’ you said, ‘a grand renascent extol’ - whatever the hell that means - you said it would be guaranteed with this project. But to put it frankly, I’m not convinced.” With this he threw down the stapled cluster of paper, the front-page imprinted with the words: Bambi live action, draft screenplay.

The agent remained still, taking only a one-second respite to glare at the harlot rooted at the adjacent table who was clamorously orating on the merits of Fritz the Cat over Felix the Cat. “Well?” Van Damme pressed, “Do I not pay you enough? I’ve just come back from filming some cack in

“Um,” the plucky undercurrent moving the agent along somewhat, “Mr Van Damme, I think we have more important issues right now than whether you may or may not take the main role in this new film. Like, look at you!” Van Damme peered down innocently for a moment. “What is with the mummy visage?” the agent continued, the restraints of meekness receding, “you look like an Osiris idiot!”

At this outright insolence, Van Damme arose and plunged his enwrapped fist into the centre of the table. Grabbing the collars of his confidant, and staring right through his pupils, Van Damme retched, “Listen, you don’t know the hell I’ve been through, the savage descents and visceral collapses penetrating my person over the last couple of weeks. The events that have lead to my current appearance have been nasty, and I now bear a massive burden…”

---

Despite the groundbreaking synopsis consorting around this film, Van Damme didn’t shake from front to rear over his role. In fact, he slinked around the prison of the production with the demeanour of a rundown janitor perpetually sanding vomit. The long carpools out to the rural set where brokered by the wraith of tense hush, where Van Damme would sit opposite his co-stars, head down, but well aware of their insidious ogles. He was alienated by his fame, with the steeples of the outsider being ridden all over his person as if harnessed by Camus himself.

Just as the miasma of despair was sinking to it’s lowest ebb, a breakthrough broke through. Following an extended day of shooting, a woesome Van Damme bobbled to his trailer, only to be met at his destination by a line-up of stuntmen and grips. They broadcast a pleasantness he had not yet seen, and invited him out to enjoy the cabarets of Estonian nightlife. Having no reason to negate this, and subtly desiring an end to his dejection, he assented, and off they travelled into the capital city

Several ale-holes were docked at, a multitude of Eastern European ladies espied upon, brawls narrowly averted, chugalugs chugged, banal anecdotes purged like diarrhoea, and backwashes of stomach reflux aching the oesophagus. All the regular activities of the lads out on the town. Feeling melancholic after a number of minor-key laments dedicated to Kickboxer in a local piano bar, Van Damme and his escorts ventured into an open-air fair bubbling with sugary corrosives and stilted former-bank managers. It was here the true motives of his comrades became apparent.

After a few orbits of the frightening locomotives, rotating wheeled monstrosities and triangulated ball games, the jobbing crewmen persuaded Van Damme to visit a mystic who was secluded in a squared tent laced with the tassels of a labyrinthine need to acquire new tassels. Drunken and soporific, he decided to appease their wishes, then with mind to succeed it with an evasive journey back to the hotel. Flitting the cobbles of curiosity, he wandered on into the tent, where he came across an antiquated seductress posed warbling cryptic charms. Feeling his presence, she beseeched him a sitting, and with an iniquitous smirk on her face, flashed a tattoo on her forearm of a nymph with spires anatomising her gentle facial features.

“Well,” said Van Damme knifing the silence, “are you going to tell me my future?” The haggard mystic looked at him. “No, I’m not that type of cliché.” Feeling slightly extraneous, Van Damme replied, “Why am I here then? What do you do?” The gaunt eyes of the mystic rolled and she spluttered, “I take monies for services rendered at first enigmatically harmless, then following gestation, erupt into full-blown afflictions.” An inebriated Van Damme fingered his crew-cut at this roundabout explanation. “Listen,” the mystic continued, “drink this fine beverage and say no more.” From the instillation of Estonian mores during his fleeting social flirtation, he knew not to examine liquor too stringently, so he grabbed the tumbler of shadowy liquid and sent it’s contents tumbling down into the abysms of his gullet.

Then a split curtain of darkness unified, and the narrative was propelled along a short ellipsis of time.

Jean-Claude Van Damme woke up in his hotel room the next morning, bile rusting his throat, and the centrifuge of his mind spinning backwards. An overflow from the lake of memory slowly made its way into his frontal lobe, and the temporary amnesia that hung over him began to dissipate. He recalled his cronies filling him with copious amounts of alcohol and then ditching him. But the events to follow remained in eclipse, mired in a cloud of black. In an attempt to ameliorate his memory, he jumped out of bed and skipped over to the divan. During this skip he noticed a perpendicular set of lines rashing his chest. Swollen red and looking like sleep-induced engraving, he decided to ignore it under the assumption that time’s great scythe would cleave it away. Hobbled by the divan, he also resolved to ignore last night’s remembered chaos, what with there being less than a fortnight till the final shots of photography, there was little need to erupt a ruckus.

Filming continued, and the crewmen returned to their stockpile of disdain, but the rash did not vanish. Within two days it had grown to encompass a large percentage of his chest. Also similar relations of this skin plague were taking up residence on his arms and legs. This was not the only peculiarity, for he was experiencing odd sounds in his head, and would even find himself saying streams of words inadvertently at random moments. Luckily his only tasks on the film were to punch and kick the antagonists, and because it was winter, he was apparelled most of the time in clothes that covered his embarrassing ailment.

One night he had a dream. He was sitting on a stool, surrounded by darkness, when suddenly the sun exploded overhead and he realised that he was on a stage in the middle of a massive horde of people, all shouting and screaming in his direction. But instead of absconding from the stage or resorting to the foetus position, he began to dazzle them with scissor-kicks and air-guitar histrionics. Gyrating under the spotlights, all fear and trepidation evaporated in an instant, and he was left to have the edification of the crowd roar fellate and cuddle him.

When his sleep fissured, he was at a loss to explain this dreamscape. Inspecting his skin malaise, he noticed a definite shaping evolving on his pectorals. The letters V and H were clearly visible, as well as some kind of wings sprouting out from behind the characters. He had also started to write down the random thoughts that recurred in his head. He now had a number of notes bearing ambiguous lines such as “I live my life like there’s no tomorrow,” and “Got it bad, got it bad, got it bad.”

“Indeed I do,” thought Van Damme humbly to himself.

To add another layer of insult to this odd injury, he would find himself playing air-guitar with any elongated shape he happened to pick up. The waitress was quite at a loss when she witnessed Van Damme executing a two-handed tapping solo on a baguette over breakfast.

Realising that something was desperately wrong - as he moved about covering random Kinks’ songs - he decided to demand an assortment of answers from his one-night friends. Clutching fists oozed in spite and repressing instinctual needs to start hollering A Minors, he confronted the miscreants, whose irksome mentalities were quickly ripped apart by force. A bloody-nosed Latvian emigrant, working as Best Boy, folded under the strains of Van Damme’s inquisition and spilled a puddle of truth. “Please don’t hit me again, I’ll tell you everything you want to know,” implored the Latvian, “We set you up to be cursed by a mystic at the fair. We paid her to enact the dreaded Van Halen hex on you.” This outlandish madness scraped itself across the countenance of Van Damme, who inquired further, “What does that mean?” “It means,” replied the maimed Latvian, “you are turning into the rock band Van Halen.”

With this revelation, Van Damme dropped the man and motioned to track down that blasphemous mystic - who now resurfaced in his memory - and demand she alleviates the curse.

Driving through the busy streets of

He halted his vehicular mobility outside of the fair and impelled his body into it’s interior. It was not long before he apprehended the mystic, and with a sly blow to the ear, he mailed her to the floor. “Remove this horrible curse right now!” bellowed an infuriated Van Damme. Ascending to her feet, she acquiesced and began concocting an antidote. Much of the rash had now climbed his neck and was now summiting on his head.

She drew a tumbler into his field of view, filled with a murky substance, and then said, “Drink this and the cure will naturally develop from your ill cells. But I have one warning for you, this remedy isn’t perfect, if you ever hear another Van Halen song, the scourge will return two-fold.” Van Damme drank the elixir.

---

“So I got a local doctor to bandage me up,” spoke a relaxed Van Damme in a restaurant just off Euphemism Boulevard, “and got on the first flight back here.” A scaffolding of awe had built up around the agent’s physiognomy, and he stuttered, “Wow, that’s some tale. Do you know how long you’ll be in this state?” Van Damme looked at him and said, “However long the organic processes take to complete their task. Don’t worry, I’ll be back to fighting shape in no time, just don’t be playing the music of those hard rockers near me anytime, alright?” “Sure,” replied the agent.

And just then, in a moment of misfortune that could only adorn a murky narrative or a cursed tale, the sweet aural melodies of 1984 began to stir in the background.